This post compares and contrasts two perspectives on how much sulforaphane is suitable for healthy people. One perspective was an October 2019 review from John Hopkins researchers who specialize in sulforaphane clinical trials:

Broccoli or Sulforaphane: Is It the Source or Dose That Matters?

These researchers didn’t give a consumer-practical answer, so I’ve presented a concurrent commercial perspective to the same body of evidence via an October 2019 review from the Australian founder of a company that offers sulforaphane products:

Sulforaphane: Its “Coming of Age” as a Clinically Relevant Nutraceutical in the Prevention and Treatment of Chronic Disease

1. Taste from a clinical trial perspective:

“Harsh taste (a.k.a. back-of-the-throat burning sensation) that is noticed by most people who consume higher doses of sulforaphane, must be acknowledged and anticipated by investigators. This is particularly so at higher limits of dosing with sulforaphane, and not so much of a concern when dosing with glucoraphanin, or even with glucoraphanin-plus-myrosinase.

Presence and/or enzymatic production of levels of sulforaphane in oral doses ranging above about 100 µmol, creates a burning taste that most consumers notice in the back of their throats rather than on the tongue. Higher doses of sulforaphane lead to an increased number of adverse event reports, primarily nausea, heartburn, or other gastrointestinal discomfort.”

Taste wasn’t mentioned in the commercial review. Adverse effects were mentioned in this context:

“Because SFN is derived from a commonly consumed vegetable, it is generally considered to lack adverse effects; safety of broccoli sprouts has been confirmed. However, use of a phytochemical in chemoprevention engages very different biochemical processes when using the same molecule in chemotherapy; biochemical behaviour of cancer cells and normal cells is very different.”

2. Commercial products from a clinical trial perspective:

“Using a dietary supplement formulation of glucoraphanin plus myrosinase (Avmacol®) in tablet form, we observed a median 20% bioavailability with greatly dampened inter-individual variability. Fahey et al. have observed approximately 35% bioavailability with this supplement in a different population.”

Avmacol appeared to be the John Hopkins product of choice, as it was mentioned 15 times in its clinical trials table. A further investigation of Avmacol showed that its supplier for broccoli extract, TrueBroc, was cofounded by a John Hopkins coauthor! Yet the review stated:

“The authors declare no conflict of interest.”

Please disclose easily discoverable ethical and commercial conflicts without prevarication. Other products were downgraded with statements such as:

“5 or 10 g/d of BroccoPhane powder (BSP), reported to be rich in SF, daily x 4 wks (we have assayed previously and found this not to be the case).”

They also disclaimed:

“We have indicated clinical studies in which label results have been used rather than making dose measurements prior to or during intervention.”

No commercial products – not even the author’s own company’s – were directly mentioned in a commercial perspective.

3. Dosage from a clinical trial perspective:

“Reporting of administered dose of glucoraphanin and/or sulforaphane is a poor measure of the bioavailable / bioactive dose of sulforaphane. As a consequence, we propose that the excreted amount of sulforaphane metabolites (sulforaphane + sulforaphane cysteine-glycine + sulforaphane cysteine + sulforaphane N-acetylcysteine) in urine over 24 h (2–3 half-lives), which is a measure of “internal dose”, provides a more revealing and likely consistent view of delivery of sulforaphane to study participants.

Only recently have there been attempts to define minimally effective doses in humans – an outcome made possible by development of consistently formulated, stable, bioavailable broccoli-derived preparations.”

Dosage from a commercial perspective:

“Of available SFN clinical trials associated with genes induced via Nrf2 activation, many demonstrate a linear dose-response. More recently, it has become apparent that SFN can behave hormetically with different effects responsive to different doses. This is in addition to its varying effects on different cell types and consequent to widely varying intracellular concentrations.

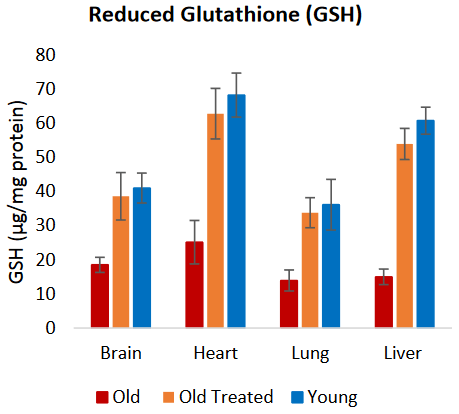

A 2017 clinical pilot study examined the effect of an oral dose of 100 μmol (17.3 mg) encapsulated SFN on GSH [reduced glutathione] induction in humans over 7 days. Pre- and postmeasurement of GSH in blood cells that included T cells, B cells, and NK cells showed an increase of 32%. Researchers found that in the pilot group of nine participants, age, sex, and race did not influence the outcome.

Clinical outcomes are achievable in conditions such as asthma with daily SFN doses of around 18 mg daily and from 27 to 40 mg in type 2 diabetes. The daily SFN dose found to achieve beneficial outcomes in most of the available clinical trials is around 20-40 mg.”

The author’s sulforaphane products are available in 100, 250, and 700 mg capsules of enzyme-active broccoli sprout powder.

4. Let’s see how these perspectives treated a 2018 Spanish clinical trial published as Effects of long-term consumption of broccoli sprouts on inflammatory markers in overweight subjects.

From a commercial perspective:

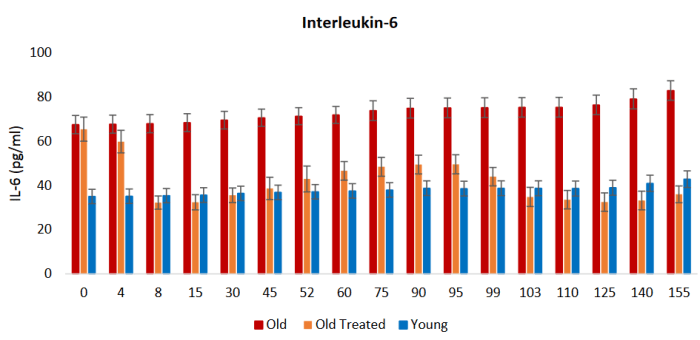

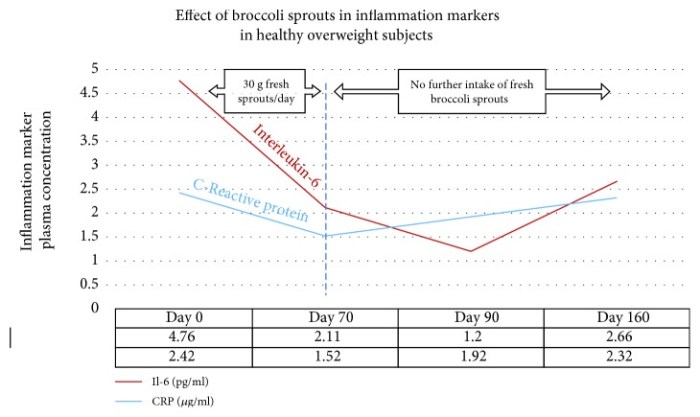

“In a recent study using 30 grams of fresh broccoli sprouts incorporated daily into diet, two key inflammatory cytokines were measured at four time points in forty healthy overweight [BMI 24.9 – 29.9] people. Levels of both interleukin-6 (Il-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP) declined over the 70 days during which sprouts were ingested.

These biomarkers were measured again at day 90, wherein it was found that Il-6 continued to decline, whereas CRP climbed again. When the final measurement was taken at day 160, CRP, although climbing, had not returned to its baseline value. Il-6 remained significantly below baseline level at day 160.

Sprouts contained approximately 51 mg (117 μmol) GRN [glucoraphanin], and plasma and urinary SFN metabolites were measured to confirm that SFN had been produced when sprouts were ingested.”

From a clinical trial perspective, glucoraphanin dosage was “1.67 (GR) μmol/kg BW.” This wasn’t accurate, however. It was assumed into existence by:

“In cases where authors did not indicate dosage in μmol/kg body weight (BW), we have made those calculations using a priori assumption of a 70 kg BW.”

117 μmol / 1.67 μmol/kg = 70 kg.

This study provided overweight subjects’ mean weight in its Table 1 as “85.8 ± 16.7 kg.” So its actual average glucoraphanin dosage per kg body weight was 117 μmol / 85.8 kg = 1.36 μmol/kg. Was making an accurate calculation too difficult?

A clinical trial perspective included this study in Section “3.2. Clinical Studies with Broccoli-Based Preparations: Efficacy” subsection “3.2.8. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome, and Related Disorders.” This was somewhat misleading, as it was grouped with studies such as a 2012 Iranian Effects of broccoli sprout with high sulforaphane concentration on inflammatory markers in type 2 diabetic patients: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial (not freely available).

A commercial perspective pointed out substantial differences between these two studies:

“Where the study described above by Lopez-Chillon et al. investigated healthy overweight people to assess effects of SFN-yielding broccoli sprout homogenate on biomarkers of inflammation, Mirmiran et al. in 2012 had used a SFN-yielding supplement in T2DM patients. Although the data are not directly comparable, the latter study using the powdered supplement resulted in significant lowering of Il-6, hs-CRP, and TNF-α over just 4 weeks.

It is not possible to further compare the two studies due to vastly different time periods over which each was conducted.”

The commercial perspective impressed as more balanced than the clinical trial perspective. The clinical trial perspective also had an undisclosed conflict of interest!

A. The clinical trial perspective:

- Effectively promoted one commercial product whose supplier was associated with a coauthor;

- Downgraded several other commercial products; and

- Tried to shift responsibility for the lack of “minimally effective doses in humans” to commercial products with:

“Only recently have there been attempts to define minimally effective doses in humans – an outcome made possible by the development of consistently formulated, stable, bioavailable broccoli-derived preparations.”

But unless four years previous is “recently,” using commercial products to excuse slow research progress can be dismissed. A coauthor of the clinical trial perspective was John Hopkins’ lead researcher for a November 2015 Sulforaphane Bioavailability from Glucoraphanin-Rich Broccoli: Control by Active Endogenous Myrosinase, which commended “high quality, commercially available broccoli supplements” per:

“We have now discontinued making BSE [broccoli sprout extract], because there are several high quality, commercially available broccoli supplements on the market.”

The commercial perspective didn’t specifically mention any commercial products.

B. The commercial perspective didn’t address taste, which may be a consumer acceptance problem.

C. The commercial perspective provided practical dosage recommendations, reflecting their consumer orientation. These recommendations didn’t address how much sulforaphane is suitable for healthy people, though.

The clinical trial perspective will eventually have to make practical dosage recommendations after they stop dodging their audience – which includes clinicians trying to apply clinical trial data – with unhelpful statements such as:

“Reporting of administered dose of glucoraphanin and/or sulforaphane is a poor measure of the bioavailable / bioactive dose of sulforaphane.”

How practical was their “internal dose” recommendation for non-researcher readers?

Here’s what I’m doing to answer how much sulforaphane is suitable for healthy people.

I’d like to posthumously credit my high school literature teachers Dorothy Jasiecki and Martin Obrentz for this post’s compare-and-contrast approach. They both required their students to read at least two books monthly, then minimally handwrite a 3-page (single-spaced) paper comparing and contrasting those books.

Each monthly assignment was individualized so that students couldn’t undo the assignment’s purpose – to think for yourself – with parasitical collaboration. This former practice remains a good measure of intentional dumbing-down of young people, the intent of which has become clearer.

You can see from these linked testimonials that their approach was in a bygone era, back when some teachers considered a desired outcome of public education to be that each individual learned to think for themself. My younger brother contributed:

“I can still remember everything Mr. Obrentz ever assigned for me to read. He was the epitome of what a teacher should be.”