It’s challenging for people to change their framework when their paychecks or mental state or reputations depend on it not changing.

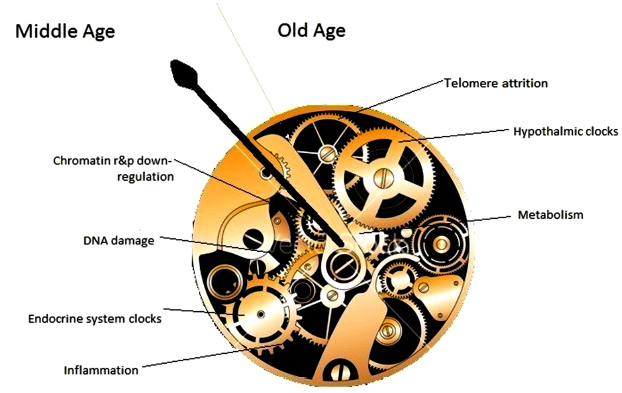

I’ll use The hypothalamus and aging as an example. This review was alright for partial fact-finding up through 2018. Its facts were limited, however, to what fit into the reviewers’ paradigm.

The 2015 An environmental signaling paradigm of aging provided examples of findings that weren’t considered in this 2018 review. It also presented a framework that better incorporated what was known in 2015.

Here’s how they viewed the same 2013 study, Hypothalamic programming of systemic ageing involving IKK-β, NF-κB and GnRH (not freely available).

Paradigm: “The hypothalamus is hypothesized to be a primary regulator of the process of aging of the entire body.”

Study assessment:

“Age-associated inflammation increase is mediated by IκB kinase-β (IKK-β) and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) in microglia and, subsequently, nearby neurons through microglia–neuron interaction in the mediobasal hypothalamus. Apparently, blocking hypothalamic or brain IKK-β or NF-κB activation causes delayed aging phenotype and improved lifespan.

Aging correlates with a decline in hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) expression in mice. Mechanistically, activated IKK-β and NF-κB significantly down-regulates GnRH transcription. GnRH therapy through either hypothalamic third ventricularor or subcutaneous injection leads to a significant recovery of neurogenesis in the hypothalamus and hippocampus, and a noticeable improvement of age-related phenotype in skin thickness, bone density, and muscle strength when applied in middle-aged mice.”

Paradigm: Environmental signaling model of aging

Study assessment:

“A link between inflammation and aging is the finding that inflammatory and stress responses activate NF-κB in the hypothalamus and induce a signaling pathway that reduces production of GnRH by neurons. GnRH decline contributes to aging-related changes such as bone fragility, muscle weakness, skin atrophy, and reduced neurogenesis. Consistent with this, GnRH treatment prevents aging-impaired neurogenesis, and decelerates aging in mice.

Zhang et al. report that there is an age-associated activation of NF-κB and IKK-β. Loss of sirtuins may contribute both to inflammation and other aspects of aging. But this explanation, also given by Zhang et al., merely moves the question to why there is a loss of sirtuins.

The case is particularly interesting when we realize that the aging phenotype can only be maintained by continuous activation of NF-κB – a product of which is production of TNF-α.

Reciprocally, when TNF-α is secreted into the inter-cellular milieu, it causes activation of NF-κB. In their study, Zhang et al. noted that activation of NF-κB began in microglia (the immune system component cells found in the brain), which secreted TNF-α, resulting in a positive feedback loop that eventually encompassed the entire central hypothalamus.

The net result of this is a diminution in production of gonadotropin-releasing factor which accounted for a shorter lifespan. Provision of GnRH eliminated that effect, while either preventing NF-κB activation (or that of the IKK-β upstream activator) or by providing gonadotropin-releasing factor directly into the brain, or peripherally, extending lifespan by about 20%.

In spite of the claim of Zhang et al. that the hypothalamus is the regulator of lifespan in mice, their experiments show that only some aspects of lifespan are controlled by the hypothalamus, as preventing NF-κB activation in this organ did not stop aging and death. Similar increased NF-κB activation with age has been seen in other tissues as well, and said to account for dysfunction in aging adrenal glands.

It was demonstrated that increased aging occurred as a result of lack of gonadotropin-releasing hormone, and that increased lifespan resulted from its provision during aging. In this manner:

- Aging of hypothalamic microglia leads to

- Aging of the hypothalamus, which leads to

- Aging elsewhere in the body.

So here we have a multi-level interaction:

- Activation of NF-κB leads to

- Cellular aging, leading to

- Diminished production of GnRH, which then

- Acts (through cells with a receptor for it, or indirectly as a result of changes to GnRH-receptor-possessing cells) to decrease lifespan.

So the age state of hypothalamic cells, at least with respect to NF-κB activation, is communicated to other cells via the reduced output of GnRH.”

Not using the same frameworks, are they?

In 2015, this researcher told the world what could be done to dramatically change the entire aging research area. He and other researchers did so recently as curated in Part 3 of Rejuvenation therapy and sulforaphane which addressed hypothalamus rejuvenation.