This 2016 New York rodent study found:

This 2016 New York rodent study found:

“Parental behavioural traits can be transmitted by non-genetic mechanisms to the offspring.

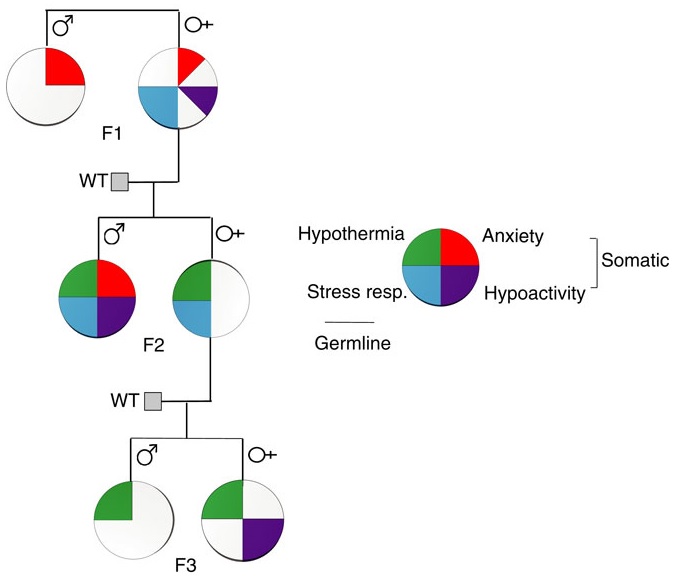

We show that four anxiety/stress-reactive traits are transmitted via independent iterative-somatic and gametic epigenetic mechanisms across multiple generations.

As the individual traits/pathways each have their own generation-dependent penetrance and gender specificity, the resulting cumulative phenotype is pleiotropic. In the context of genetic diseases, it is typically assumed that this phenomenon arises from individual differences in vulnerability to the various effects of the causative gene. However, the work presented here reveals that pleiotropy can be produced by the variable distribution and segregated transmission of behavioural traits.”

A primary focus was how anxiety was transmitted from parents to offspring:

“The iterative propagation of the male-specific anxiety-like behaviour is most compatible with a model in which proinflammatory state is propagated from H [serotonin1A receptor heterozygote] F0 to F1 [children] females and in which the proinflammatory state is acquired by F1 males from their H mothers, and then by F2 [grandchildren] males from their F1 mothers.

We propose that increased levels of gestational MIP-1β [macrophage inflammatory protein 1β] in H and F1 mothers, together with additional proinflammatory cytokines and bioactive proteins, are required to produce immune system activation in their newborn offspring, which in turn promotes the development of the anxiety-like phenotype in males.

In particular, increase in the number of monocytes and their transmigration to the brain parenchyma in F1 and F2 males could be central to the development of anxiety.”

The researchers studied transmission of behavioral traits and epigenetic changes. Due to my quick take on the study title – “Behavioural traits propagate across generations..” – I had expectations of this study that weren’t born out. What could the researchers have done versus what they did?

The study design removed prenatal and postnatal parental behavioral transmission of behavioral traits and epigenetic changes as each generation’s embryos were implanted into foster wild-type (WT) mothers.

The study design substituted the foster mothers’ prenatal and postnatal parental environments for the biological parents’ environments. So we didn’t find out, for example:

- To what extents the overly stress-reactive F1 female children’s prenatal environments and postnatal behaviors induced behaviors and/or epigenetic changes in their children; and

- Whether the F2 grandchildren’s parental behaviors subsequently induced behaviors and/or epigenetic changes in the F3 great-grandchildren.

How did the study meet the overall goal of rodent studies: to help humans?

-

- Only a minority of humans experienced an early-life environment that included primary caregivers other than our biological parents.

- Very, very few of us experienced a prenatal environment other than our biological mothers.

- The study’s thorough removal of parental behavior was an outstanding methodology to confirm by falsifiability whether parental behavior was both an intergenerational and transgenerational epigenetic inheritance mechanism.

- Maybe the researchers filled in some gaps in previous rodent studies, such as determining what is or isn’t a “true transgenerational mechanism.”

As an example of a rodent study that more closely approximated human conditions, the behavior of a mother whose DNA was epigenetically changed by stress induced the same epigenetic changes to her child’s DNA when her child was stressed per One way that mothers cause fear and emotional trauma in their infants:

“Our results provide clues to understanding transmission of specific fears across generations and its dependence upon maternal induction of pups’ stress response paired with the cue to induce amygdala-dependent learning plasticity.”

How did parental behavioral transmission of behavioral traits and epigenetic changes become a subject not worth investigating? These traits and effects can be seen everyday in real-life human interactions, and in every human’s physiology.

But when investigating human correlates with behavioral epigenetic changes of rodents in the laboratory, parental behavioral transmission of behavioral traits is often treated the way this study treated it: as a confounder.

I doubt that people who have reached some degree of honesty about their early lives and concomitant empathy for others would agree with this prioritization. The papers of Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance week show the spectrum of opportunities to advance science that were intentionally missed.

http://www.nature.com/ncomms/2016/160513/ncomms11492/full/ncomms11492.html “Behavioural traits propagate across generations via segregated iterative-somatic and gametic epigenetic mechanisms”