This 2017 review laid out the tired, old, restrictive guidelines by which current US research on the epigenetic effects of stress is funded. The reviewer rehashed paradigms circumscribed by his authoritative position in guiding funding, and called for more government funding to support and extend his reach.

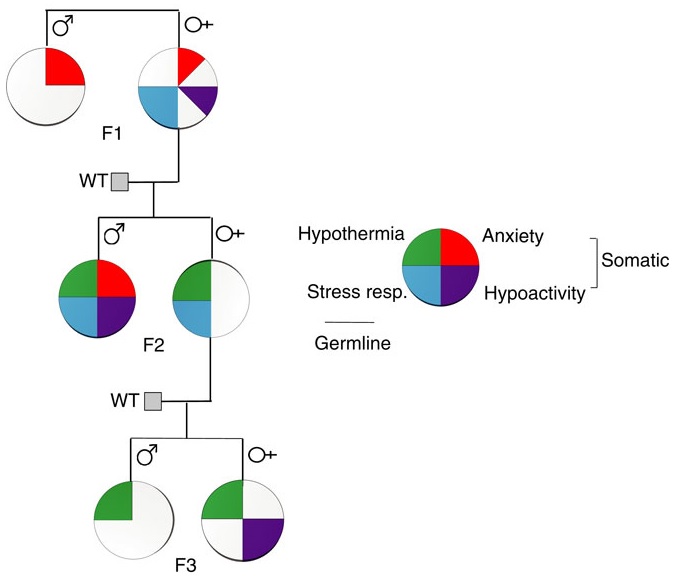

The reviewer won’t change his beliefs regarding individual differences and allostatic load pictured above since he helped to start those memes. US researchers with study hypotheses that would develop evidence beyond such memes may have difficulties finding funding except outside of his sphere of influence.

Here’s one example of the reviewer’s restrictive views taken from the Conclusion section:

“Adverse experiences and environments cause problems over the life course in which there is no such thing as “reversibility” (i.e., “rolling the clock back”) but rather a change in trajectory [10] in keeping with the original definition of epigenetics [132] as the emergence of characteristics not previously evident or even predictable from an earlier developmental stage. By the same token, we mean “redirection” instead of “reversibility”—in that changes in the social and physical environment on both a societal and a personal level can alter a negative trajectory in a more positive direction.”

What would happen if US researchers proposed tests of his “there is no such thing as reversibility” axiom? To secure funding, the prospective studies’ experiments would be steered toward altering “a negative trajectory in a more positive direction” instead.

An example of this influence may be found in the press release of Familiar stress opens up an epigenetic window of neural plasticity where the lead researcher stated a goal of:

“Not to ‘roll back the clock’ but rather to change the trajectory of such brain plasticity toward more positive directions.”

I found nothing in citation [10] (of which the reviewer is a coauthor) where the rodent study researchers even attempted to directly reverse the epigenetic changes! The researchers under his guidance simply asserted:

“A history of stress exposure can permanently alter gene expression patterns in the hippocampus and the behavioral response to a novel stressor”

without making any therapeutic efforts to test the permanence assumption!

Never mind that researchers outside the reviewer’s sphere of influence have done exactly that, reverse both gene expression patterns and behavioral responses!!

In any event, citation [10] didn’t support an “there is no such thing as reversibility” axiom.

The reviewer also implied that humans respond just like lab rats and can be treated as such. Notice that the above graphic conflated rodent and human behaviors. Further examples of this inappropriate rodent / human merger of behaviors are in the Conclusion section.

What may be a more promising research approach to human treatments of the epigenetic effects of stress? As pointed out in The current paradigm of child abuse limits pre-childhood causal research:

“If the current paradigm encouraged research into treatment of causes, there would probably already be plenty of evidence to demonstrate that directly reducing the source of the damage would also reverse damaging effects. There would have been enough studies done so that the generalized question of reversibility wouldn’t be asked.

Aren’t people interested in human treatments of originating causes so that their various symptoms don’t keep bubbling up? Why wouldn’t research paradigms be aligned accordingly?”

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2470547017692328 “Neurobiological and Systemic Effects of Chronic Stress”