This 2015 US/Canadian rodent study investigated the effects of natural variation in maternal care:

“The effects of early life rearing experience via natural variation in maternal licking and grooming during the first week of life on behavior, physiology, gene expression, and epigenetic regulation of Oxtr [oxytocin receptor gene] across blood and brain tissues (mononucleocytes, hippocampus, striatum, and hypothalamus).

Rats reared by high licking-grooming (HL) and low licking-grooming (LL) rat dams exhibited differences across study outcomes:

- LL offspring were more active in behavioral arenas,

- Exhibited lower body mass in adulthood, and

- Showed reduced corticosterone responsivity to a stressor.

Oxtr DNA methylation was significantly lower at multiple CpGs in the blood of LL versus HL males, but no differences were found in the brain. Across groups, Oxtr transcript levels in the hypothalamus were associated with reduced corticosterone secretion in response to stress, congruent with the role of oxytocin signaling in this region.

Methylation of specific CpGs at a high or low level was consistent across tissues, especially within the brain. However, individual variation in DNA methylation relative to these global patterns was not consistent across tissues.

These results suggest that:

- Blood Oxtr DNA methylation may reflect early experience of maternal care, and

- Oxtr methylation across tissues is highly concordant for specific CpGs, but

- Inferences across tissues are not supported for individual variation in Oxtr methylation.

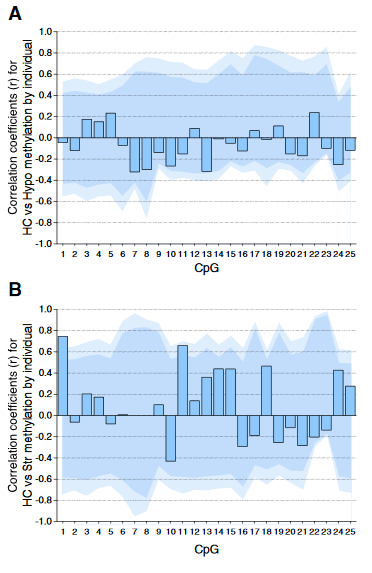

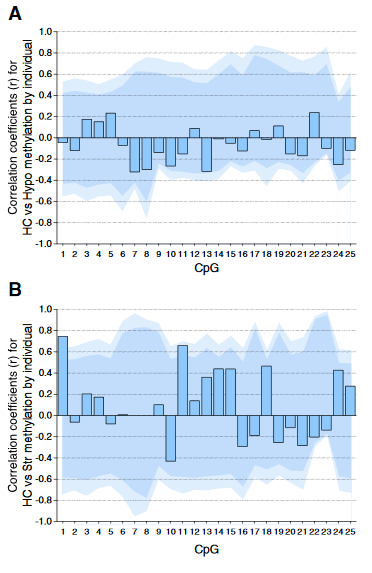

Individual DNA methylation values were not correlated across brain tissues, despite tissue concordance at the group level.

For each CpG, we computed the Pearson correlation coefficient r between methylation values for matched samples in pairs of brain regions (bars). Dark and light shaded regions represent 95% and 99% thresholds, respectively, of distributions of possible correlation coefficients determined from 10,000 permutations of the measured values among the individuals. These distributions represent the null hypothesis that an individual DNA methylation value in one brain region does not help to predict the value in another region in the same animal.

(A) Correlations based on pyrosequencing data for matched samples passing validation in both hippocampus (HC) and hypothalamus (Hypo). Correlations for individuals at each CpG were either weak (.2 < r < .3) or absent (r < .2), and none were significant, even prior to correction for multiple comparisons.

(B) Correlations for matched samples passing validation in both hippocampus and striatum (Str). Two correlations (CpG 1 and 11) were individually significant prior to but not following correction, and this result could be expected by chance.

Correlations between hippocampus and blood (described in the text) yielded similar results, and no particular CpG yielded consistently high correlation across multiple tissues.”

The study focused on whether or not an individual’s experience-dependent oxytocin receptor gene DNA methylation in one of the four studied tissues could be used to infer a significant effect in the three other tissues. The main finding was NO, it couldn’t!

The researchers’ other findings may have been strengthened had they also examined causes for the observed effects. The “natural variation in maternal licking and grooming” developed from somewhere, didn’t it?

The subjects’ mothers were presumably available for the same tests as the subjects, but nothing was done with them. Investigating at least one earlier generation may have enabled etiologic associations of “the effects of early life rearing experience” and “individual variation in DNA methylation.”

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0018506X1500118X “Natural variation in maternal care and cross-tissue patterns of oxytocin receptor gene methylation in rats” (not freely available)