This 2018 Swiss rodent study found:

“Our data show that:

- A subset of memory recall–induced neurons in the DG [dentate gyrus] becomes reactivated after memory attenuation,

- The degree of fear reduction positively correlates with this reactivation, and

- The continued activity of memory recall–induced neurons is critical for remote fear memory attenuation.

Although other brain areas such as the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala are likely to be implicated in remote fear memories and remain to be investigated, these results suggest that fear attenuation at least partially occurs in memory recall–induced ensembles through updating or unlearning of the original memory trace of fear.

These data thereby provide the first evidence at an engram-specific level that fear attenuation may not be driven only by extinction learning, that is, by an inhibitory memory trace different from the original fear trace.

Rather, our findings indicate that during remote fear memory attenuation both mechanisms likely coexist, albeit with the importance of the continued activity of memory recall–induced neurons experimentally documented herein. Such activity may not only represent the capacity for a valence change in DG engram cells but also be a prerequisite for memory reconsolidation, namely, an opportunity for learning inside the original memory trace.

As such, this activity likely constitutes a physiological correlate sine qua non for effective exposure therapies against traumatic memories in humans: the engagement, rather than the suppression, of the original trauma.”

The researchers also provided examples of human trauma:

The researchers also provided examples of human trauma:

“We dedicate this work to O.K.’s father, Mohamed Salah El-Dien, and J.G.’s mother, Wilma, who both sadly passed away during its completion.”

So, how can this study help humans? The study had disclosed and undisclosed limitations:

1. Humans aren’t lab rats. We can ourselves individually change our responses to experiential causes of ongoing adverse effects. Standard methodologies can only apply external treatments.

2. It’s a bridge too far to go from neural activity in transgenic mice to expressing unfounded opinions on:

“A physiological correlate sine qua non for effective exposure therapies against traumatic memories in humans.”

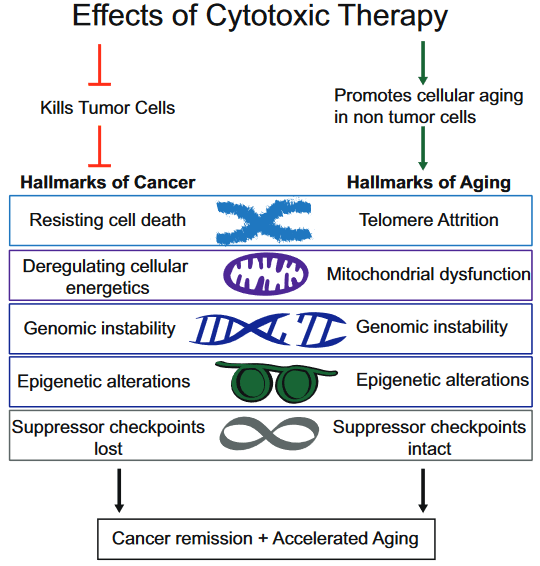

Human exposure therapies have many drawbacks, in addition to being applied externally to the patient on someone else’s schedule. A few others were discussed in The role of DNMT3a in fear memories:

- “Inability to generalize its efficacy over time,

- Potential return of adverse memory in the new/novel contexts,

- Context-dependent nature of extinction which is widely viewed as the biological basis of exposure therapy.”

3. Rodent neural activity also doesn’t elevate recall to become an important goal of effective human therapies. Clearly, what the rodents experienced should have been translated into human reliving/re-experiencing, not recall! Terminology used in animal studies preferentially has the same meaning with humans, since the purpose of animal studies is to help humans.

4. The researchers acknowledged that:

“Other brain areas such as the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala are likely to be implicated in remote fear memories and remain to be investigated.”

A study that provided evidence for basic principles of Primal Therapy determined another brain area:

“The findings imply that in response to traumatic stress, some individuals, instead of activating the glutamate system to store memories, activate the extra-synaptic GABA system and form inaccessible traumatic memories.”

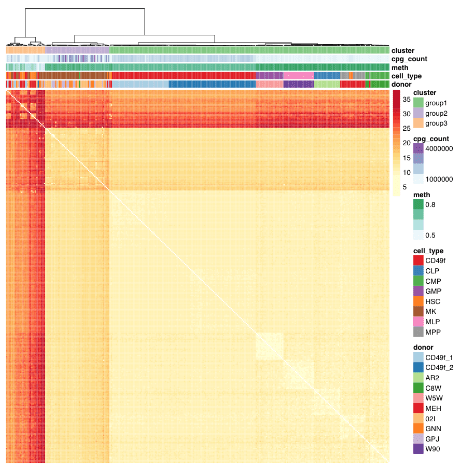

The study I curated yesterday, Organ epigenetic memory, demonstrated organ memory storage. It’s hard to completely rule out that other body areas may also store traumatic memories.

The wide range of epigenetic memory storage vehicles is one reason why effective human therapies need to address the whole person, the whole body, and each individual’s entire history.

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/360/6394/1239 “Reactivation of recall-induced neurons contributes to remote fear memory attenuation” (not freely available)

Here’s one of the researchers’ outline:

This post has somehow become a target for spammers, and I’ve disabled comments. Readers can comment on other posts and indicate that they want their comment to apply here, and I’ll re-enable comments.