This 2016 Swiss review of enduring memories demonstrated what happens when scientists’ reputations and paychecks interfered with them recognizing new research and evidence in their area but outside their paradigm: “A framework containing the basic assumptions, ways of thinking, and methodology that are commonly accepted by members of a scientific community.”

A. Most of the cited references were from decades ago that established these paradigms of enduring memories. Fine, but the research these paradigms excluded was also significant.

B. All of the newer references were continuations of established paradigms. For example, a 2014 study led by one of the reviewers found:

“Successful reconsolidation-updating paradigms for recent memories fail to attenuate remote (i.e., month-old) ones.

Recalling remote memories fails to induce histone acetylation-mediated plasticity.”

The researchers elected to pursue a workaround of the memory reconsolidation paradigm when the need for a new paradigm of enduring memories directly confronted them!

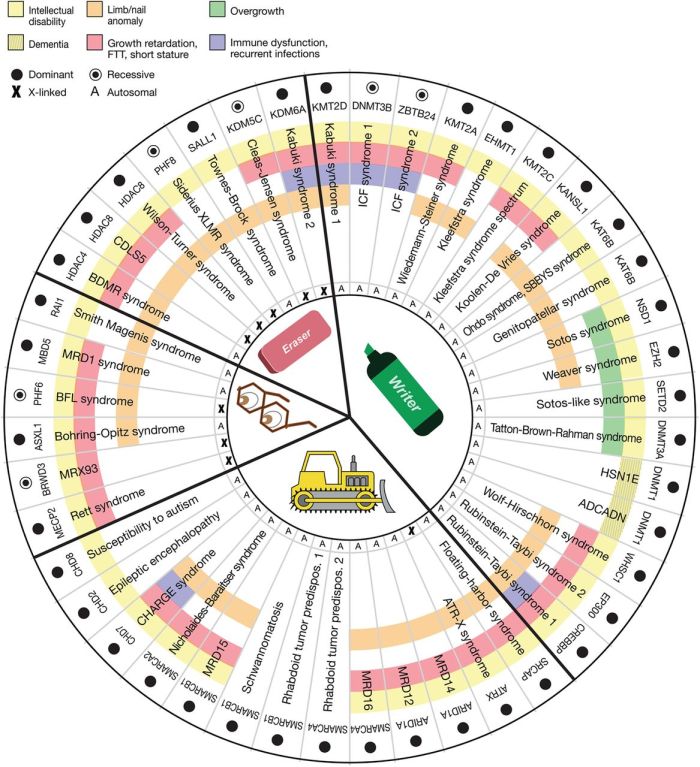

C. None of the reviewers’ calls for further investigations challenged existing paradigms. For example, when the reviewers suggested research into epigenetic regulation of enduring memories, they somehow found it best to return to 1984, a time when dedicated epigenetics research had barely begun:

“Whether memories might indeed be ‘coded in particular stretches of chromosomal DNA’ as originally proposed by Crick [in 1984] and if so what the enzymatic machinery behind such changes might be remain unclear. In this regard, cell population-specific studies are highly warranted.”

Two examples of relevant research the review failed to consider:

1. A study that provided evidence for basic principles of Primal Therapy went outside existing paradigms to research state-dependent memories:

“If a traumatic event occurs when these extra-synaptic GABA receptors are activated, the memory of this event cannot be accessed unless these receptors are activated once again.

It’s an entirely different system even at the genetic and molecular level than the one that encodes normal memories.”

What impressed me about that study was the obvious nature of its straightforward experimental methods. Why hadn’t other researchers used the same methods decades ago? Doing so could have resulted in dozens of informative follow-on study variations by now, which is my point in Item A. above.

2. A relevant but ignored 2015 French study What can cause memories that are accessible only when returning to the original brain state? which supported state-dependent memories:

“Posttraining/postreactivation treatments induce an internal state, which becomes encoded with the memory, and should be present at the time of testing to ensure a successful retrieval.”

The review also showed the extent to which historical memory paradigms depend on the subjects’ emotional memories. When it comes to human studies, though, designs almost always avoid studying emotional memories.

It’s clearly past time to Advance science by including emotion in research.

http://www.hindawi.com/journals/np/2016/3425908/ “Structural, Synaptic, and Epigenetic Dynamics of Enduring Memories”