Here are five 2025 human ergothioneine studies, starting with a clinical trial of healthy older adults:

“In this 16-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 147 adults aged 55–79 with subjective memory complaints received ergothioneine (10 mg or 25 mg/day ErgoActive®) or placebo. Across all the groups, approximately 73% of participants in each group were female, with a median age of 69 years.

The primary outcome was the change in composite memory. Secondary outcomes included other cognitive domains, subjective memory and sleep quality, and blood biomarkers. At baseline, participants showed slightly above-average cognitive function (neurocognitive index median = 105), with plasma ergothioneine levels of median = 1154 nM.

Although not synthesized in the human body, ergothioneine is efficiently absorbed via the OCTN1 transporter (also known as the ergothioneine transporter, or ETT), which is expressed in many tissues, including the intestine, red blood cells, kidneys, bone marrow, immune cells, skin, and brain. This transporter enables ergothioneine to accumulate in high concentrations in organs vulnerable to oxidative stress and inflammation. Ergothioneine has multiple cellular protective functions, including scavenging reactive oxygen species, chelating redox-active metals, suppressing pro-inflammatory signaling, and protecting mitochondrial function.

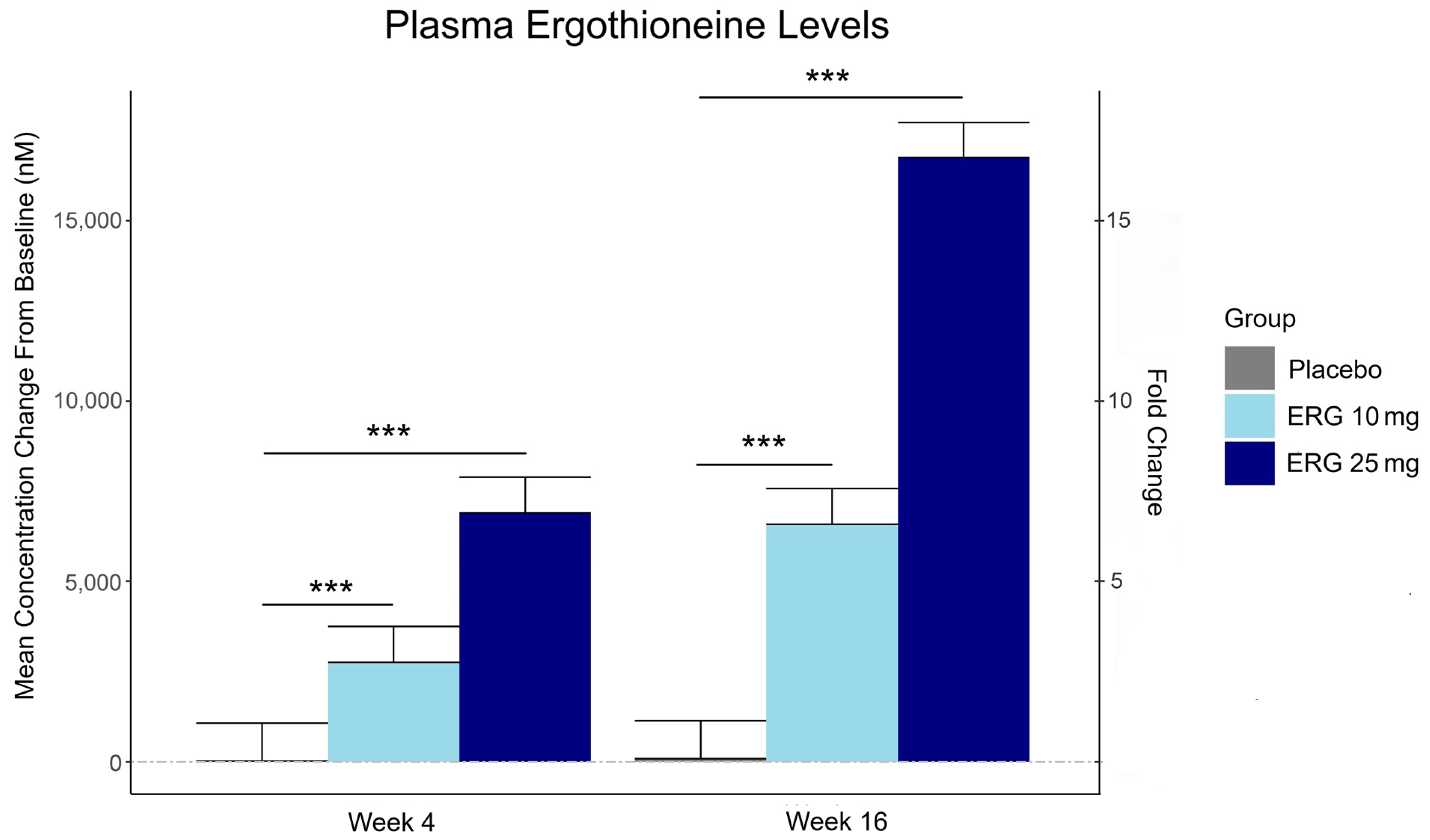

Plasma ergothioneine increased by ~3- and ~6-fold for 10 mg, and ~6- and ~16-fold for 25 mg, at weeks 4 and 16, respectively.

While the primary outcome, composite memory, showed early improvement in the 25 mg group compared to baseline, this effect was not sustained and did not differ from placebo. Reaction time showed a significant treatment-by-time interaction favoring ergothioneine, yet the between-group differences were not significant, suggesting that any potential benefits were modest and require validation in larger or longer studies.

Other cognitive effects observed were primarily within-group and not consistently dose-responsive, highlighting the challenge of detecting objective cognitive changes over a relatively short study duration in high-functioning healthy populations. However, positive effects of ergothioneine supplementation were observed on subjective measures of prospective memory and sleep initiation that were not seen in the placebo group.

This trial adds to the growing body of evidence supporting the favorable safety profile of ergothioneine. No adverse events attributable to ergothioneine were reported. Additionally, we observed potential hepatoprotective effects, with significant reductions in the plasma AST and ALT levels, particularly among males in the ERG 25 mg group.”

https://www.mdpi.com/1661-3821/5/3/15 “The Effect of Ergothioneine Supplementation on Cognitive Function, Memory, and Sleep in Older Adults with Subjective Memory Complaints: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial”

The third graphic for Ergothioneine dosing, Part 2 showed a human study where a 25 mg dosing stopped after Day 7, but the plasma ergothioneine level stayed significantly higher than baseline through Day 35.

The second graphic for Ergothioneine dosing, Part 2 was a male mouse experiment where plasma ergothioneine levels of a human equivalent 22 mg to 28 mg daily dose kept rising through 92 weeks.

This trial couldn’t explain the desirability of a 25 mg daily dose that was likely (per the second and third graphics for Ergothioneine dosing, Part 2) to sustain the subjects’ increased plasma ergothioneine levels well after the trial ended at Week 16. What effects can be expected from a sustained plasma ergothioneine level that’s 16 times higher than the subjects’ initial levels? Were these 16-fold sustained plasma ergothioneine levels better or worse than the 6-fold increases in the 10 mg group, both of which were likely to continue past the trial’s end?

A representative of the trial’s sponsoring company talked a little more about the trial in this interview:

Another clinical trial investigated ergothioneine’s effects on skin:

“We conducted an 8-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial to evaluate effects of daily oral supplementation with 30 mg of ergothioneine (DR.ERGO®) on skin parameters in healthy adult women aged 35–59 years who reported subjective signs of skin aging. Objective measurements including melanin and erythema indices, skin glossiness, elasticity, and wrinkle and pigmentation counts were used to comprehensively evaluate changes in skin condition.

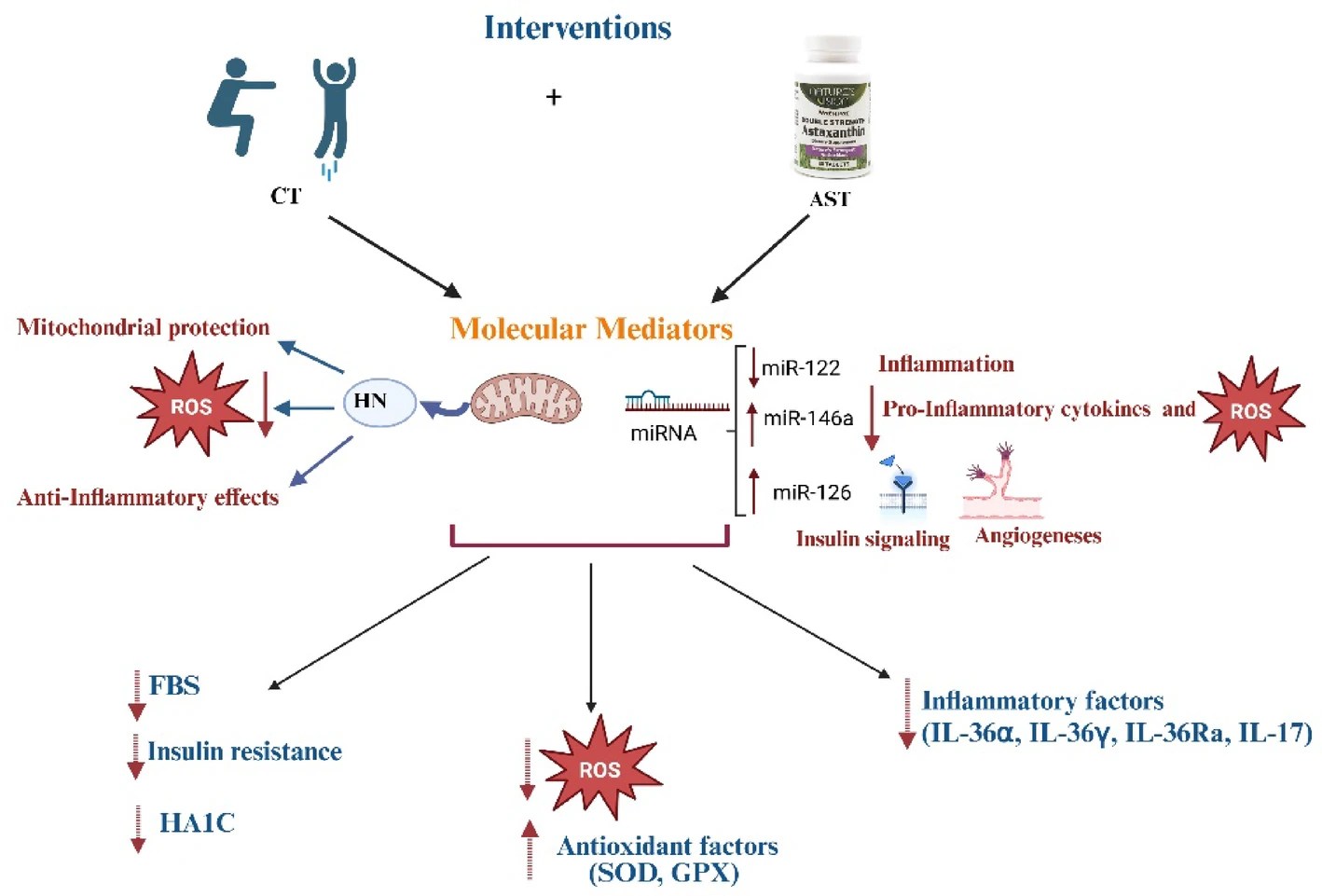

The OCTN1 transporter is preferentially expressed in basal and granular epidermal layers, where cellular renewal and barrier maintenance are most active. Once internalized, ergothioneine localizes to mitochondria, where it directly scavenges reactive oxygen species (ROS) and protects mitochondrial DNA from UV- and inflammation-induced damage.

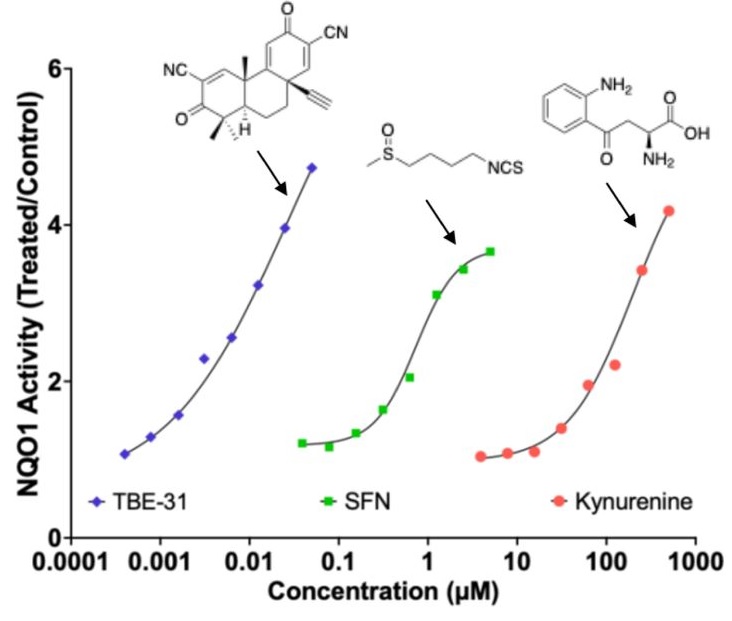

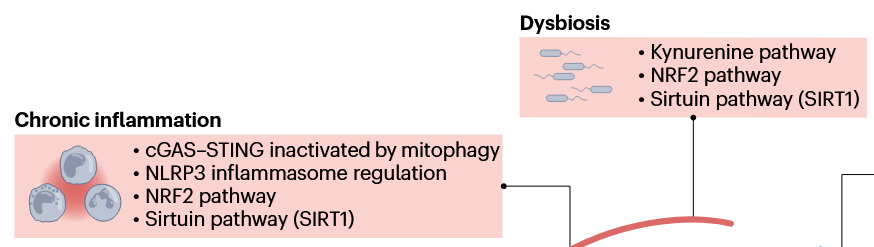

At the signaling level, ergothioneine activates key protective pathways such as the Nrf2/ARE axis, enhancing expression of antioxidant enzymes including HO-1, NQO1, and γ-GCLC. These enzymes contribute to redox homeostasis and glutathione regeneration, reinforcing cellular defense systems against photoaging and environmental insult.

In parallel, ergothioneine modulates the PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 and SIRT1/Nrf2 pathways, which are implicated in collagen preservation, inflammation resolution, and mitochondrial maintenance. These pathways converge to reduce matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity, enhance collagen synthesis, and suppress pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β), all of which are central to maintaining skin structure and function.

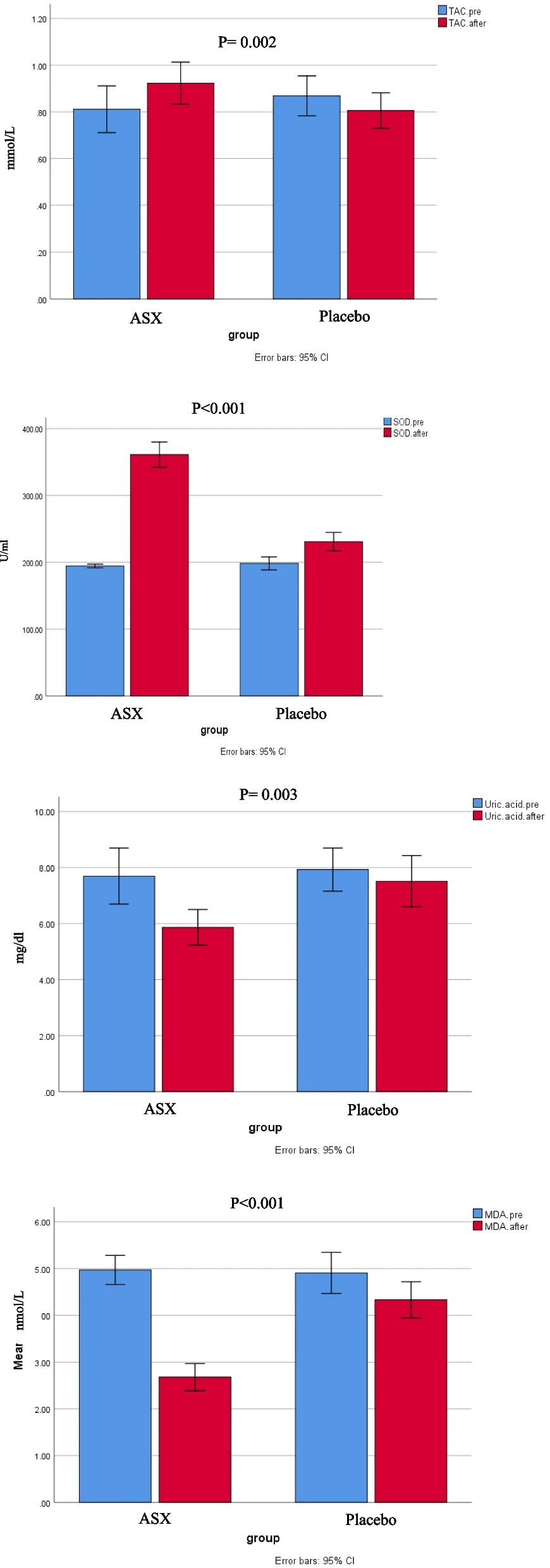

Compared to placebo, the DR.ERGO® ergothioneine group showed significantly greater improvements in melanin and erythema reduction, skin glossiness, elasticity, and wrinkle and spot reduction. No adverse events were reported.

These findings corroborate and extend previous clinical evidence from (Hanayama et al., 2024), who investigated an ergothioneine-rich mushroom extract (Pleurotus sp., 25 mg ergothioneine/day) in a 12-week randomized double-blind trial, and (Chunyue Zhang, 2023), who examined pure ergothioneine supplementation (25 mg/day) in a 4-week open-label study. We contextualized our results within this existing literature by comparing key outcomes.

Several limitations should be acknowledged:

- The study cohort consisted solely of Japanese women aged 35–59 years, which may limit generalizability across sexes, ethnicities, and age groups.

- The 8-week intervention period, while sufficient to detect short-term effects, does not allow conclusions about the sustainability of benefits or the risk of relapse upon discontinuation.

- The placebo group also showed modest improvements in self-perception, highlighting the well-documented placebo response in beauty and wellness studies.

- This study focused on a single daily dosage (30 mg/day) without evaluating dose–response relationships, and hydration-specific endpoints such as corneometry or transepidermal water loss (TEWL) were not included.”

https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.10.16.25337962v1.full-text “Effects of Continuous Oral Intake of DR.ERGO® Ergothioneine Capsules on Skin Status: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial”

I read the compared 2024 trial, Effects of an ergothioneine-rich Pleurotus sp. on skin moisturizing functions and facial conditions: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. I’d guess there was a bit of cognitive dissonance in the women in the placebo group who disrupted their lives every day for 12 weeks to dutifully eat 21 tablets of what was glucose and caramel, not hiratake mushroom powder.

Two clinical trials investigated ergothioneine’s effects on sleep quality:

“A four-week administration of 20 mg/day ergothioneine (EGT), a strong antioxidant, improves sleep quality; however, its effect at lower doses remains unclear. This study estimated the lower effective doses of EGT using a physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model in two clinical trials.

In Study 1, participants received 5 or 10 mg/day of EGT for 8 weeks, and their plasma and blood EGT concentrations were measured. An optimized PBPK model incorporating absorption, distribution, and excretion was assembled. Our results showed that 8 mg/day of EGT for 16 weeks was optimal for attaining an effective plasma EGT concentration.

In Study 2, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, participants received 8 mg/day EGT or a placebo for 16 weeks. The subjective sleep quality was significantly improved in the EGT group than in the placebo group.

In mammals, EGT is not generated in the body but is acquired from the diet via the carnitine/organic cation transporter OCTN1/SLC22A4. Its plasma concentration after oral administration is quite stable and gradually increases after repeated dosing on a multi-day basis.

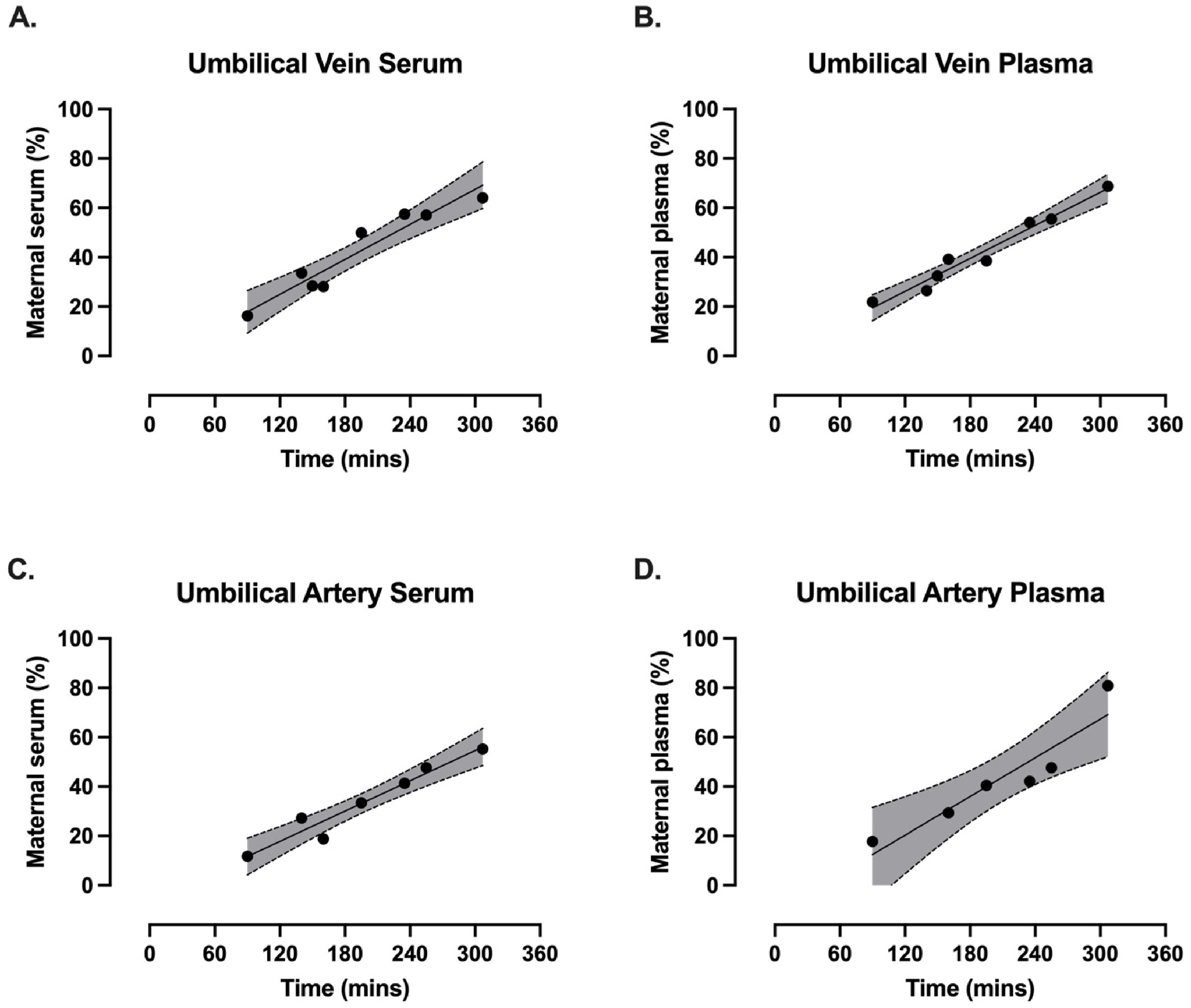

Blood concentrations of EGT increase after Day 8 when EGT intake is interrupted, and they continue to increase until Day 35. The delayed increase in EGT concentration in the blood, compared with that in the plasma, can be interpreted as its efficient uptake by undifferentiated blood cells, which express high levels of OCTN1/SLC22A4 in the bone marrow, and subsequent differentiation to mature blood cells that enter the circulation. This may imply the nonlinear absorption, distribution, and excretion of EGT owing to saturation of the transporter at higher concentrations, potentially leading to difficulty in model construction.

This is the first study to propose a strategy to estimate lower effective doses based on the PBPK model.”

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/fsn3.70382 “Estimation and Validation of an Effective Ergothioneine Dose for Improved Sleep Quality Using Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model”

The bolded section above referenced a 2016 study / third graphic for Ergothioneine dosing, Part 2, where a 25 mg dosing stopped after Day 7, but the plasma ergothioneine level stayed high through Day 35. I didn’t see that the referenced 2004 and 2010 studies addressed this 2016 finding.

I also didn’t see that this study’s mathematical model accounted for saturation of the OCTN1 transporter or other effects, such as a very small ergothioneine clearance rate. Okay, lower the ergothioneine dose, and achieve a lower persistent plasma ergothioneine level, to what benefit?

The referenced 2004 paper, Expression of organic cation transporter OCTN1 in hematopoietic cells during erythroid differentiation, concluded:

“The present study demonstrated that OCTN1 is associated with myeloid cells rather than lymphoid cells, and especially with erythroid-lineage cells at the transition stage from immature erythroid cells to peripheral mature erythrocytes.”

Persistent high ergothioneine levels aren’t costless. Skewing bone marrow stem cells and progenitor cells toward a myeloid lineage is done at the expense of lymphocytes, T cells, B cells, and other lymphoid lineages.

Where are the studies that examine these tradeoffs? Subjective sleep quality in this study and sleep initiation in the first study above aren’t sufficiently explanatory.

A study investigated associations of plasma ergothioneine levels and cognitive changes in older adults over a two-year period:

“Observational studies have found that lower plasma levels of ergothioneine (ET) are significantly associated with higher risks of neurodegenerative diseases. However, several knowledge gaps remain:

- Most of the above studies were based on cross-sectional study design, and potential reverse causation cannot be excluded. It has been suggested that plasma ET declines concomitantly with the deterioration of cognitive function.

- Since the impact of a single dietary factor on health is mild, it is prone to be affected by the baseline characteristics of subjects (such as sex, educational level, disease status and gene polymorphism). However, no study has systematically evaluated potential effect modifiers on the association between ET levels and cognitive function.

- The dose-response distribution between ET and cognitive function remains undetermined.

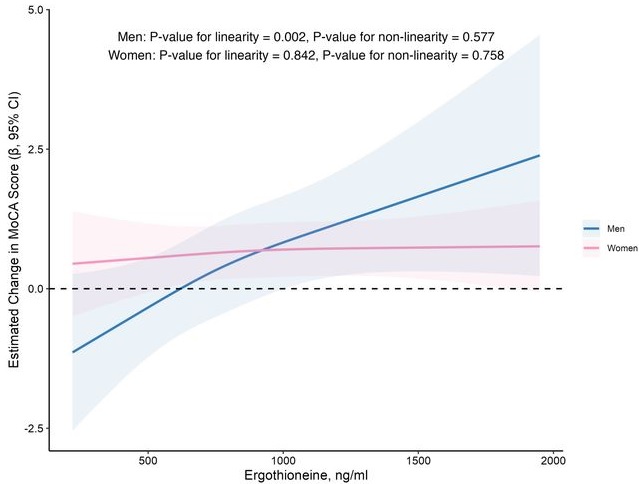

In this prospective cohort study of 1,131 community-dwelling older adults (mean age 69 years), higher baseline plasma ET levels were significantly associated with slower cognitive decline, as assessed by Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scores, during a 2-year follow-up period.

When the plasma concentration of ET exceeds 1,000 ng/mL, the decline in cognitive function significantly slows down. However, this association has only been observed in men.

Domain-specific analysis found that the observed ET-MoCA association was mainly driven by the temporary slowdown in the decline of visuospatial/executive and delayed recall. Impaired delayed recall represents one of the earliest and most sensitive cognitive markers of dementia progression, predictive of conversion from MCI to dementia. The preferential preservation of this function by ET suggests targeted neuroprotective effects within the hippocampus.

Visual inspection of the spline curves revealed a potential plateauing effect at ET concentrations ≥1,000 ng/mL in the total population.

Baseline ET concentrations differed between men and women. Most men (81.5%) had concentrations below 1,000 ng/mL (median 754.2, IQR 592.0–937.9 ng/mL). Women exhibited substantially higher median plasma ET concentrations than men, with 35.7% of women exceeded 1,000 ng/mL (median 890.1, IQR 709.7–1,095.6 ng/mL).

Our study included only participants with normal cognitive function, and the results remained robust even after excluding those with baseline cognitive function at the lower end of the normal range. Collectively, our findings support that low ET intake occurs prior to cognitive decline.

Our findings indicate that higher plasma ET levels are significantly associated with slower cognitive decline independent of confounders in non-demented community-dwelling elderly participants, with such association observed in men but not women. Dose-response curves indicated plateauing effects above 1000 ng/mL.”

https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.07.16.25331363v2 “Associations of plasma ergothioneine levels with cognitive function change in non-demented older Chinese adults: A community-based longitudinal study”

The average age of this study and the first trial above were both 69 years. Since the first trial’s participants showed slightly above-average cognitive function (neurocognitive index median = 105), with plasma ergothioneine levels of median = 1154 nM at baseline, and this study showed plateauing effects above 1000 ng/mL, I wonder how raising plasma ergothioneine levels above 1000 ng/mL could possibly show a net benefit for older people? What are the trade-offs for older people between potentially increasing slightly above-average cognitive function with ergothioneine and its other effects from saturating their OCTN1 transporter?

This study is at its preprint stage. I’m interested to see if its peer review prompts these researchers to also investigate the common finding that people who are most deficient at baseline have the greatest improvements. If so, would these sex-specific associations still hold?

Wrapping up with a study that investigated associations of serum ergothioneine levels with the risk of developing dementia:

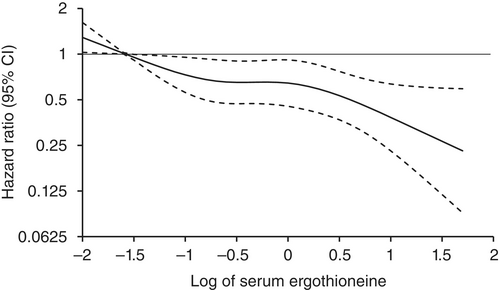

“1344 Japanese community-residents aged 65 years and over, comprising 765 women and 579 men, without dementia at baseline were followed prospectively for a median of 11.2 years.

During follow-up, 273 participants developed all-cause dementia. Among them, 201 had Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and 72 had non-Alzheimer’s disease (non-AD) dementia.

Age- and sex-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for all-cause dementia, AD, and non-AD dementia decreased progressively across increasing quartiles of serum ergothioneine. These associations remained significant after adjustment for a wide range of cardiovascular, lifestyle, and dietary factors, including daily vegetable intake.

In subgroup analysis, association between serum ergothioneine levels and the risk of dementia tended to be weaker in older participants and in women:

- In older individuals, cumulative burden of multiple risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and smoking may contribute to both neurodegenerative and vascular pathology, potentially diminishing the relative influence of ergothioneine.

- In women, postmenopausal hormonal changes, particularly the decline in estrogen, have been associated with increased oxidative stress and a higher vulnerability to neurodegenerative changes.

Several limitations should be noted:

- Since serum ergothioneine levels and other risk factors were measured only at baseline, we could not evaluate the changes of serum ergothioneine levels during the follow-up period. Lifestyle modifications during follow-up could have influenced serum ergothioneine levels and other risk factors. In addition, serum ergothioneine level was measured only once, and from a sample.

- We cannot rule out residual confounding factors, such as other nutrients in mushrooms and socioeconomic status.

- There is a possibility that dementia cases at the prodromal stage were included among participants with low serum ergothioneine levels at baseline.

- We are unable to specify which mushroom varieties were predominantly consumed by participants in the town of Hisayama.

- Given the limited discriminative ability of serum ergothioneine and potential degradation due to long-term sample storage, we were unable to explore a clinically meaningful threshold value of serum ergothioneine.

- Generalizability of findings was limited because participants of this study were recruited from one town in Japan.

These findings suggest that the potential benefit of ergothioneine may be attenuated in individuals with pre-existing, multifactorial risk profiles for dementia.

Our findings showed that higher serum ergothioneine levels were associated with a lower risk of developing all-cause dementia, AD, and non-AD dementia in an older Japanese population. Since ergothioneine cannot be synthesized in the human body, a diet rich in ergothioneine may be beneficial in reducing the risk of dementia.”

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/pcn.13893 “Serum ergothioneine and risk of dementia in a general older Japanese population: the Hisayama Study”

For five years I got most of my estimated 7 mg daily ergothioneine intake from mushrooms in AGE-less chicken vegetable soup per Ergothioneine dosing. The soup was always boring, but I got too bored this year and stopped making it. I haven’t replaced mushroom intake with supplements.

I still don’t eat fried or baked foods, preferring sous vide and braising cooking methods to avoid exogenous advanced glycation end products. I avoid buying foods that evoke a hyperglycemic response or otherwise form excessive endogenous AGEs per All about AGEs.