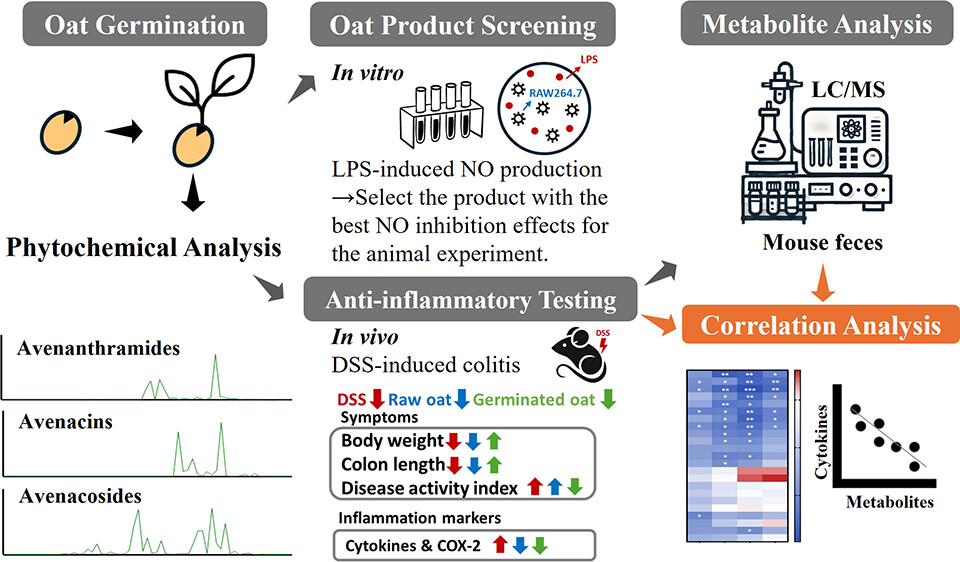

A 2025 rodent study investigated differing effects of regular oats and oat sprouts to treat induced colitis:

“This study aims to test our hypothesis that germinated oats exert stronger anti-inflammatory effects than raw oats due to their higher levels of bioactive phytochemicals. First, the nitric oxide (NO) production assay was used to screen [22] commercially available oat seed products and identify the product with the highest anti-inflammatory activity after germination [for five days]. The selected oat seed product was then produced in larger quantities and further evaluated in an in vivo study using the dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis mouse model to compare the anti-inflammatory effects of phytochemical extracts from germinated and raw oats.

The guideline states that for a healthy U.S.-style dietary pattern at a 2000 calorie level, a daily intake of 6 ounces of grains is recommended, with at least 3 ounces (84 g) coming from whole grains (WGs). For a 60 kg human, consuming 3 ounces of WGs per day translates to a 17.2 g/kg daily dose in mice. Given that the daily food intake of a 20 g mouse is approximately 2.5 g, the 17.2 g/kg daily dose corresponds to 14% of the total diet as WGs. Therefore, the 7 and 21% WG equivalent doses used in this study are relevant to human consumption.

Germination led to an overall increase in the content of all avenanthramides (AVAs) and avenacins (AVCs) as well as some avenacosides (AVEs):

- For AVAs, the compounds 2c, 2p, 2f, 2cd, 2pd, and 2fd significantly increased by 10.0-, 6.3-, 9.6-, 20.7-, 10.6-, and 4.6-fold, respectively, which is consistent with previous reports.

- This study is the first to report an increase in AVCs after germination, with AVC-A2, B2, A1, and B1 contents significantly increasing by 2.5-, 2.2-, 3.6-, and 4.2-fold, respectively.

- Although germination resulted in a decrease in certain AVEs, it significantly increased the levels of AVE-C, Iso-AVE-A, AVE-E, and AVE-F by 1.8-, 3.3-, 3.3-, and 5.0-fold, respectively. Notably, AVE-E has been previously reported to have the strongest anti-inflammatory activity among all of the major AVEs.

In summary, germination enhances the anti-inflammatory properties of oats in both cells and DSS-induced colitis in mice by increasing levels of bioactive phytochemicals. Correlation analysis showed a significant inverse relationship between pro-inflammatory cytokines and phytochemical content in feces, especially AVAs and their microbial metabolites.

The observation of a stronger anti-inflammatory effect in the low-dose germinated oat group compared with the high-dose group is intriguing and warrants further investigation. One possible explanation is the phenomenon of hormesis, where low doses of bioactive compounds can exert beneficial effects, while higher doses may lead to diminished efficacy or even adverse effects. Further studies involving a broad range of doses would be valuable to define the effective intake range and provide insight into the underlying mechanisms.

It is possible that AVAs, AVEs, and AVCs act synergistically to enhance the overall anti-inflammatory efficacy, potentially by targeting different inflammatory pathways or modulating each other’s bioavailability and activity. Further investigation into the synergistic interactions among these compounds is warranted.”

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jafc.5c02993 “Phytochemical-Rich Germinated Oats as a Novel Functional Food To Attenuate Gut Inflammation”

I’ve eaten 3-day-old Avena sativa oat sprouts (started from 20 grams of groats) every day for 4.5 years now, and haven’t had gut problems. Here’s what they looked like this morning: